Private Chain assembly

Miden assembly is a simple, low-level language for writing programs for Miden VM. It stands just above raw Miden VM instruction set, and in fact, many instructions of Miden assembly map directly to raw instructions of Miden VM.

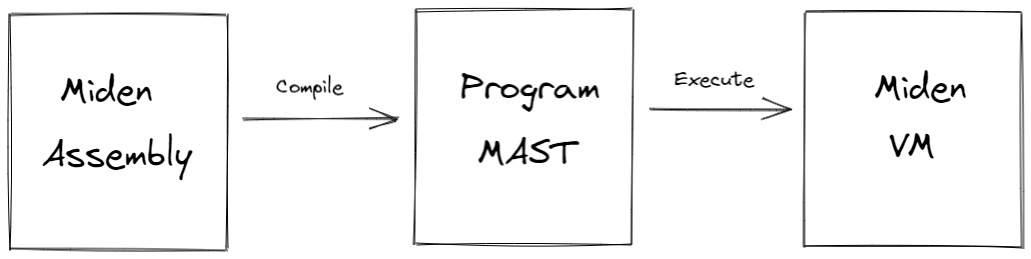

Before Miden assembly can be executed on Miden VM, it needs to be compiled into a Program MAST (Merkelized Abstract Syntax Tree) which is a binary tree of code blocks each containing raw Miden VM instructions.

As compared to raw Miden VM instructions, Miden assembly has several advantages:

- Miden assembly is intended to be a more stable external interface for the VM. That is, while we plan to make significant changes to the underlying VM to optimize it for stability, performance etc., we intend to make very few breaking changes to Miden assembly.

- Miden assembly natively supports control flow expressions which the assembler automatically transforms into a program MAST. This greatly simplifies writing programs with complex execution logic.

- Miden assembly supports macro instructions. These instructions expand into short sequences of raw Miden VM instructions making it easier to encode common operations.

- Miden assembly supports procedures. These are stand-alone blocks of code which the assembler inlines into program MAST at compile time. This improves program modularity and code organization.

The last two points also make Miden assembly much more concise as compared to the raw program MAST. This may be important in the blockchain context where pubic programs need to be stored on chain.

Terms and notations¶

In this document we use the following terms and notations:

- \(p\) is the modulus of the VM’s base field which is equal to \(2^{64} - 2^{32} + 1\).

- A binary value means a field element which is either \(0\) or \(1\).

- Inequality comparisons are assumed to be performed on integer representations of field elements in the range \([0, p)\).

Throughout this document, we use lower-case letters to refer to individual field elements (e.g., \(a\)). Sometimes it is convenient to describe operations over groups of elements. For these purposes we define a word to be a group of four elements. We use upper-case letters to refer to words (e.g., \(A\)). To refer to individual elements within a word, we use numerical subscripts. For example, \(a_0\) is the first element of word \(A\), \(b_3\) is the last element of word \(B\), etc.

Design goals¶

The design of Miden assembly tries to achieve the following goals:

- Miden assembly should be an easy compilation target for high-level languages.

- Programs written in Miden assembly should be readable, even if the code is generated by a compiler from a high-level language.

- Control flow should be easy to understand to help in manual inspection, formal verification, and optimization.

- Compilation of Miden assembly into Miden program MAST should be as straight-forward as possible.

- Serialization of Miden assembly into a binary representation should be as compact and as straight-forward as possible.

In order to achieve the first goal, Miden assembly exposes a set of native operations over 32-bit integers and supports linear read-write memory. Thus, from the stand-point of a higher-level language compiler, Miden VM can be viewed as a regular 32-bit stack machine with linear read-write memory.

In order to achieve the second and third goals, Miden assembly facilitates flow control via high-level constructs like while loops, if-else statements, and function calls with statically defined targets. Thus, for example, there are no explicit jump instructions.

In order to achieve the fourth goal, Miden assembly retains direct access to the VM stack rather than abstracting it away with higher-level constructs and named variables.

Lastly, in order to achieve the fifth goal, each instruction of Miden assembly can be encoded using a single byte. The resulting byte-code is simply a one-to-one mapping of instructions to their binary values.